Jay-Z’s Roc Nation remade the Super Bowl halftime show, but NFL’s record on race casts long shadow

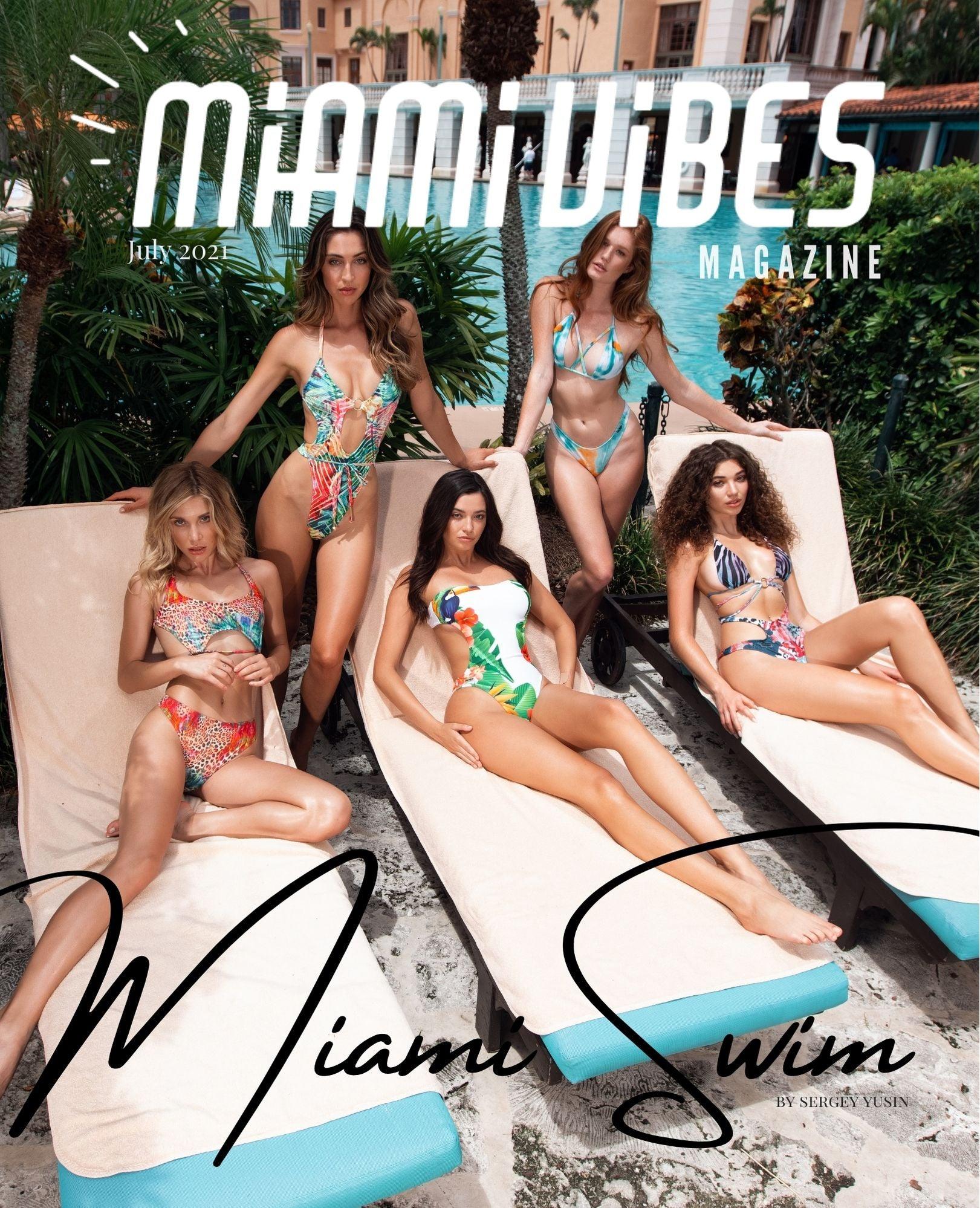

The team behind the Super Bowl halftime show, from left, Jeannae Rouzan-Clay,producer; Adam Blackstone, musical director; Dionne Harmon, co-executive producer; Desiree Perez, CEO, Roc Nation; Jesse Collins, executive producer; Bruce Rodgers, production designer; Jana Fleishman, executive vice president, Roc Nation; and Lila Nikole, wardrobe stylist.

The paint was still wet on the field at SoFi Stadium as Desiree Perez strode toward the 50-yard line, a pair of ringing-and-dinging smartphones tucked inside her boxy leather handbag.

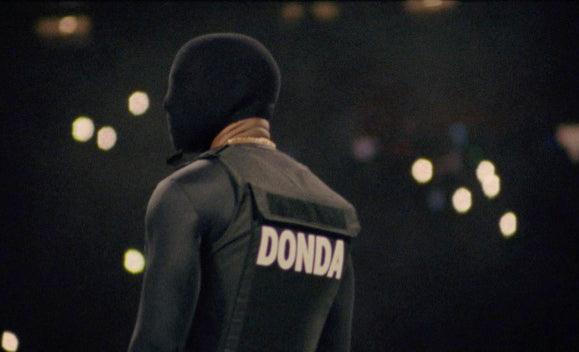

Perez, the chief executive of Roc Nation, superstar rapper Jay-Z’s wide-ranging entertainment firm, had dropped in at the Inglewood stadium last week as part of preparation for the Super Bowl halftime show her company is producing for Sunday’s game — an all-star hip-hop blowout featuring Dr. Dre, who helped pioneer West Coast rap while coming up in nearby Compton, along with Snoop Dogg, Eminem, Mary J. Blige and Kendrick Lamar.

It was just past 8 a.m., but already there were set pieces to approve, musical mixes to hear, sight lines to investigate — and, as one NFL rep gently reminded Perez, freshly sprayed turf to avoid spiking with her stiletto heels.

“It’s a lot of moving parts,” she said of the elaborate production that will take place halfway through the Los Angeles Rams’ championship battle against the Cincinnati Bengals. Behind Perez, 53, the words “END RACISM” stood out starkly against the vivid blue and white of the Rams’ end zone. “But it’s important for the time we live in,” she added. “It’s important for what we represent.”

Roc Nation’s partnership with the National Football League, which the two organizations struck three years ago, is perhaps an unlikely alliance: In 2018, after turning down an offer to headline the halftime show, Jay-Z famously rapped, “I said no to the Super Bowl / You need me, I don’t need you.”

Now, Roc Nation is working toward what might be its biggest achievement yet: the Super Bowl’s first real-deal hip-hop halftime show, decades into the genre’s domination of pop music.

“This moment is definitely overdue,” Perez said.

What’s more, the team in charge of the show is led by women and people of color, a sign of longed-for change behind the scenes at the NFL, which for years has drawn criticism for consolidating power in the hands of white men.

For all the apparent progress, though, this year’s halftime show comes amid a major development that calls into question the commitment to diversity that the league envisioned by recruiting Roc Nation.

This month, former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores sued the NFL and its 32 teams in federal court, alleging that he and other Black coaches had been blocked from high-level leadership positions due to discriminatory hiring practices. Approximately 70% of NFL players are Black, while the league had only two Black head coaches this season.

Hiring decisions are not within Roc Nation’s purview, Perez was quick to point out in an interview at SoFi alongside Jesse Collins, another of the halftime show’s executive producers. (Jay-Z declined to comment for this story.) But by lending his unique credibility to the league’s stated attempt to address its history of racial inequity — a move that raised eyebrows among many observers, even as they acknowledged his influence — the chart-topping rapper and activist has led some to wonder about his ability to impact a hidebound organization.

In 2019, Jay-Z said in a press release that the NFL had the “opportunity to inspire change across the country” and that the partnership would “strengthen the fabric of communities across America.” NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell added that Jay-Z’s “perspective is going to drive us.”

“I remember when they announced this, you said, ‘Well, it’s certainly gonna be some great halftime shows,’” said Kenneth Shropshire, who leads the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. “But on the other stuff, did Roc Nation overpromise on what they could accomplish?”

The company’s partnership with the NFL was controversial from the beginning: Roc Nation — which encompasses a record label, a sports agency and a talent-management company with clients including Rihanna, Megan Thee Stallion and NBA star LaMelo Ball — teamed with the league after former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick was more or less blacklisted as a result of the much-discussed protest movement he sparked against police violence and racial injustice.

In 2020, Jay-Z told the New York Times that he could weather “a couple rounds of negative press” — accusations, that is, that he’d sold out Kaepernick for an unspecified paycheck from the NFL — if he was able to use the league’s enormous platform to bring attention to the plight of marginalized people. Entering risky business deals wasn’t new for Jay-Z; he’d earlier launched the streaming service Tidal, which got off to a bumpy start, with complaints about its interface and royalty rates, before establishing a small if loyal user base.

Asked last week about choosing to throw in with the NFL in the wake of its rough patch over Kaepernick, Perez, who typically avoids speaking to the media — “I just don’t like the limelight for myself,” she insists — said, “It was more than a rough patch. And it was a difficult decision for us. They were being accused of all these terrible things that we stand against. We had to say, ‘Wow, they’re being boycotted by artists.’” (Rihanna said she passed on the 2019 halftime show in solidarity with Kaepernick; Maroon 5 ended up playing that year’s show to largely negative reviews.)

“But we obviously decided for going after what we feel is right and what we think we can do to make change,” Perez continued. “Let’s say for a second that this was a cynical move by the NFL — they just wanted to use us [to repair the league’s image]. OK. As long as we can go in and do things they would not normally do — if we can reach people that we normally wouldn’t reach with a message — then that for us is success.”

There’s no question that Roc Nation has reshaped the closely scrutinized halftime show both in front of and behind the cameras. In the 15 years after Janet Jackson and Justin Timberlake’s notorious 2004 “wardrobe malfunction” — an incident for which Jackson bore the brunt of the NFL’s condemnation — only four artists of color headlined the show; the three shows Roc Nation has produced have all been headlined by artists of color.

After years of pop and rock acts booked by other producers, Roc Nation has also made the show more reflective of an era when hip-hop rules streaming services; the company has sought too to make a performance reflect the Super Bowl’s host city, as when Lopez and Shakira played in Miami.

This year, Perez said, the show is “a nod to California culture,” with Dre and Lamar, who’s also from Compton, and Long Beach’s Snoop Dogg. Eminem and Blige complete a lineup that Perez said emphasizes “raw rap, raw music. There isn’t any filter to this.” Before Sunday’s game, Black country singer Mickey Guyton, who has spoken openly about prejudice in Nashville, will perform the national anthem.

Those involved were tight-lipped about the content of the show. Adam Blackstone, the music director, promised a “live experience” that draws on the tightly woven instrumentation of Dre’s studio sound as heard in classic 1990s G-funk tracks like “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang.” Collins, who has worked on the Oscars and the BET Awards, said he’s looking to tell a story about Dre’s long career and his many artistic relationships, “wrapped around some of the biggest records of all time, with a massive amount of production.” Others on the team — whose demographics contrast with a recent UCLA study that said creators of color in broadcast television are outnumbered 4 to 1 by white creators — include creative director Es Devlin, who has collaborated with the Weeknd and Adele, and choreographer Fatima Robinson, a veteran known for her work with Michael Jackson and Aaliyah.

Steve Berman — a longtime Interscope Records exec who helped shepherd Dre, Snoop, Eminem and Lamar to stardom — said, “Landing the Super Bowl halftime is without a doubt the biggest stage in any artist’s career.” Planning for this show, he added, began about two years ago. He called Roc Nation “an artist-first company” and hailed it for “understanding the artist’s way by respecting their creative vision.”

Said Perez: “Jay has changed halftime in a way that it’s less NFL, which I think they love. I think they want to be less hands-on. They know what they do well and what they don’t, and creative isn’t one of them.”

What’s less clear is Roc Nation’s role in matters of racial equity and workplace culture. Dasha Smith, the NFL’s chief people officer, said Jay-Z and Perez “have challenged us to think differently than we have in the past and, frankly, have spent a lot of time educating us on how we should be thinking about being as inclusive as possible.”

As part of the companies’ pact, Roc Nation asked Goodell to spend $100 million on various social causes over 10 years; Smith said she expects the league will reach the goal sooner than that.

Yet the Flores lawsuit draws attention to problems inside the NFL. Asked how she reacted to the news, Perez said, “I’m the CEO of a company that has a sports agency component to it, so I’d heard the whole situation. I wasn’t surprised. The number of teams and the number of Black and brown coaches — that’s math. That’s not a point of view. But now it’s out, so let’s talk about it.

“I know some owners; I don’t know every owner in the league. But just like the world, there’s a little bit of everything. There’s people that stand for things that I don’t believe in. So I wouldn’t be shocked, out of 32 owners, that potentially there is a team ownership that doesn’t want a Black coach.”

Perez, who last year had a decades-old narcotics conviction pardoned by then-President Trump, said she understands the idea that a Roc Nation halftime show, as seen against the backdrop of those coaching stats, might represent “mixed messaging.”

“Maybe some people wish we would say, ‘We’re not gonna have anything to do with halftime unless you hire 10 Black coaches,’” she said. “But I don’t know that that’s realistic.” More effective, in her view, is “keeping that chair in the room. I want to keep that position that I have to make that phone call. If tomorrow I find out something crazy, then I can pick up the phone and say, ‘Excuse me, Roger, what is going on? Is that really your policy?’”

Justin Tinsley, who writes about sports and culture for ESPN’s the Undefeated, said three years may be too soon to judge Roc Nation’s effect on a cartel-like organization that rakes in more than $10 billion a year.

“If it leads to some momentous change 10 years down the road, we can say, ‘Hey, Jay-Z helped spearhead that,’” Tinsley said. “But if the next three, four, five years yield the same uncertainty as the first three, I do wonder how he’ll look back at his decision.”

That timeline seems to suit Perez.

“We’ll take the harder, longer, rockier path, because this isn’t about walking away,” she said. “This isn’t about putting our heads down and saying, ‘We give up.’ This is about us speaking up and fighting back.”